Fitness

Great American eclipse was, like, wooaahhh

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/ERO6M4XZKLZQ4JOUYT2ETL43BE.jpg)

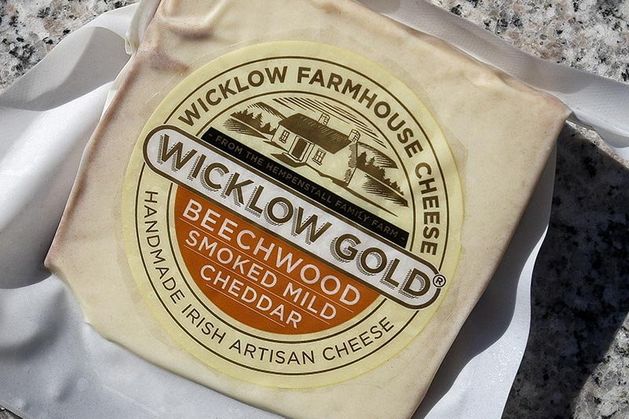

It was just as promised. An exhibition from the heavens passed over a small patch of earth on the edge of Lake Erie and left everyone standing gazing up in hokey glasses, happily dumbfounded. Even the dogs. The DJ in the amphitheatre had the good sense to stop playing for the great event. Shortly after three, the temperatures began to cool. The blotting out of the sun quickened. And then it just happened. The world about us turned dark and chilly. The moon was framed by a perfect orb. There wasn’t anything to do but shut up and gaze.

“That was otherworldly,” Leah Delano from Washington DC said afterwards.

“It was being part of a universe that you didn’t know existed,” smiled her friend, Nancy Chapman. They had been asked to put into words what is, in essence, a wordless experience. All around them, people searched for explanations for what they had just seen.

“What it’s like for me is: we are standing here, and we see this blue sky and clouds and it’s a normal day. And in minutes, it turns dark, night and stars. And you realise: that’s a reality that’s out there that we just don’t see. And now we are back to normal. And it is like okay, we came out of that. But for me, the heaviest moment, even heavier than the corona, were those few minutes when it was utter darkness. That was just: woaaahh! Because if you didn’t know that the light was going to come back, you would be thinking … holy … we are in such deep doo-doo right now,” Delano explained.

And that’s the point. Monday’s Great American Eclipse was unique in that it was far-out and nerdy and a little bit spooky all at once. It’s a day that will remain important in astronomy circles and will have a lasting impact on the millions lucky enough to experience it. Naturally, the various towns and cities have used it as a tourist attraction and Erie enjoyed a novel swell in early April numbers. But everyone understood that they were participating in a rare day.

It had started out bleakly by Lake Erie, with rain and morning cloud cover. The visitors came anyway. On the waterfront, a row of stargazers sat in camping chairs behind a row of serious looking telescopes. One of those, Vincent Filigenzi, travelled up from Long Island, New York with friends to witness this. “March 7th, 1970,” he replied immediately when asked if he ever experienced an eclipse before. He was studying astronomy at Adelphi University that year. “And there was a total eclipse at Virginia Beach. And the Prof said: let’s rent a bus and go down as a class. Sunny day. National Geographic was set up down at the beach. And it was just beautiful.”

When we chatted, at about 1.30pm, the cloud cover was still heavy, but he was completely sanguine about what he might witness on the shores of Erie.

“Who has it better than us, you know? To be in the path of a total solar … people come from all over the world to see this.”

There has been a lot of talk about the unifying effect of what is a large-scale astronomical phenomenon. Thirty-two million Americans live under the 115-mile ribbon of earth that spanned North America and which, for a few hours, was graced as the “path of totality”. Ordinary places – forgotten places, often – rendered extraordinary for a few minutes by the confluence of sun and moon.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/QEHF3V2I7IDMRDUKKWB74O6DQA.jpg)

An imprecise number of millions of visitors ditched work and worries for the day to make sure they were under that ribbon too. And it was that thought – of 30 million other people experiencing the same wonder that brought this small park into the grander experience.

The fabulously elemental science behind it elevated the entire spectacle into real-life make-believe. It was as close as anyone could ever actually get to becoming Elliot on the bicycle with a charismatic extraterrestrial in his basket. It was a stupefyingly beautiful sight.

And it was possible to be sceptical until the very last second. It was possible to think that you were about to see just another sunset, only quicker. And therefore, it was possible to be underwhelmed, and even bored at 3:11pm and to then be completely overwhelmed – silenced, reduced, convinced, grateful, even blessed – four minutes later. No dogs barked during the magical four minutes, but they were standing and their ears were alert and when it started to turn dark they wore the universal canine expression of “I’m not sure what’s going on here but I’m not certain it’s going be any good for me”. The people around them, though, lost it.

The weird thing was that even with a shard of sunlight visible, the park remained bright, if overcast. The flip to totality was sudden and people became either awestruck or lapsed into stream of consciousness. A random selection of the voices around during the four minutes when Liberty park fell under the spell of complete darkness and the cornea – the perfect golden ring of sunlight around the moon – became visible:

“You can see it shrinking!”, “Thirty seconds”, “Oh my gosh, look at the horizon!”, “It’s happening!”, “Oh my God!”, “Woah. Woah. Look at that! Look. At. That!”, “The birds are so f***ing confused, the birds are like: what the hell is happening, bro?”

People broke from gazes that were worshipful only to have a quick scan around them for affirmation that others were seeing this too: that they hadn’t entered some sort of hypnotic state. It was real and the state of bliss, with that perfect orb of light and darkness visible everywhere lasted just long enough to contain a tinge of melancholy because everyone knew that the magic had to leave momentarily; that the shadow would lift and normality – the remnants of an everyday Monday – would return.

“It was about the joy,” said Nancy Chapman.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/3TWXXJ526FGW3AEYJQRM6HUXZU.jpg)

“It was spectacular. But the joy. The instinctive human response of everybody that was shared by everybody here to scream and shout and be amazed altogether as part of humanity.”

So, in Erie and in other places under the trippy shadow path where people cried and danced and exchanged wedding vows and drank beers and lay on picnic blankets, the Great American Eclipse was just as the Nasa boffins had predicted. It was, as their official statement concluded, like: Wooaahhh.